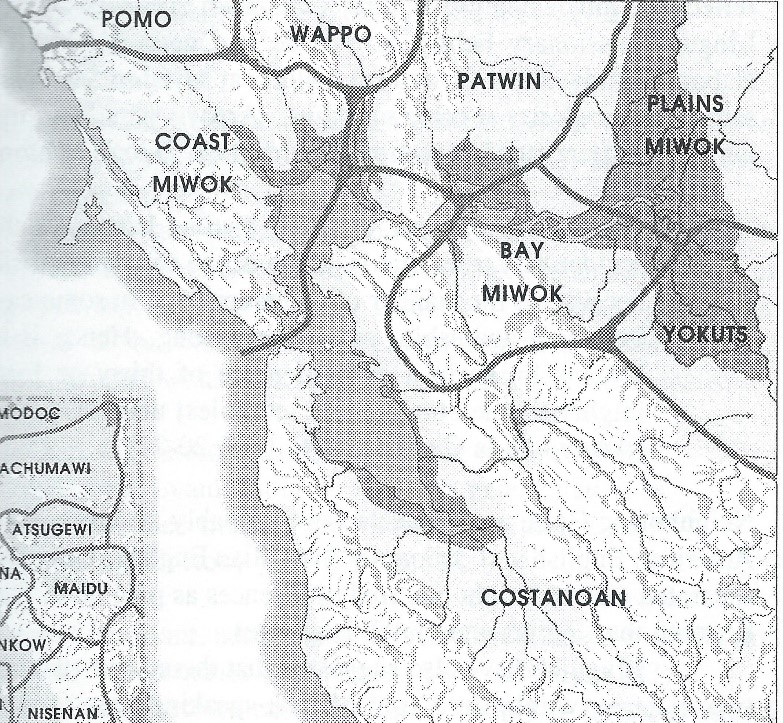

Much of present-day Contra Costa County is the aboriginal territory of the Bay Miwok culture. The lands where Lafayette and Walnut Creek are now located is the homeland of the Saklan, a tribelet of the Bay Miwok people who flourished in this area for thousands of years. Before European contact, the Bay Miwok language was one of several indigenous languages of the Bay Area, a thriving network of indigenous cultures connected through trade, intermarriage, cultural ceremonies, and diplomacy. Neighboring tribes included the Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone/Costanoan people to the west and south, Coast Miwok and Patwin-speaking tribes in the North Bay, and Plains Miwok, Sierra Miwok, and Yokuts tribes to the east in the Central Valley and Sierra foothills.

Bay Miwok territory stretched from the Oakland-Berkeley hills in the west to the Mt. Diablo foothills and San Joaquin delta in the east. A particularly sacred site in the mythology of the indigenous peoples of the East Bay is Mt. Diablo, known as Tuyshtak in the Chochenyo language, and understood to be the site of creation of the world and humanity.

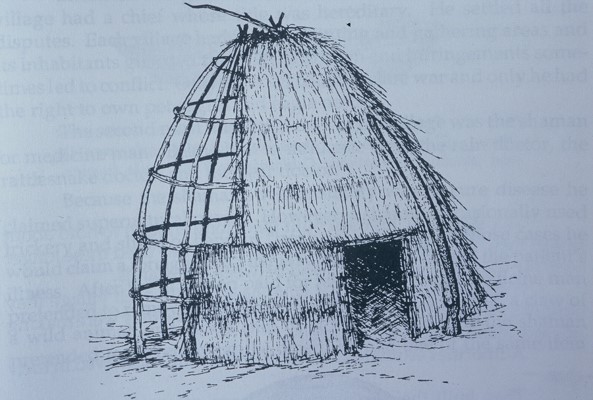

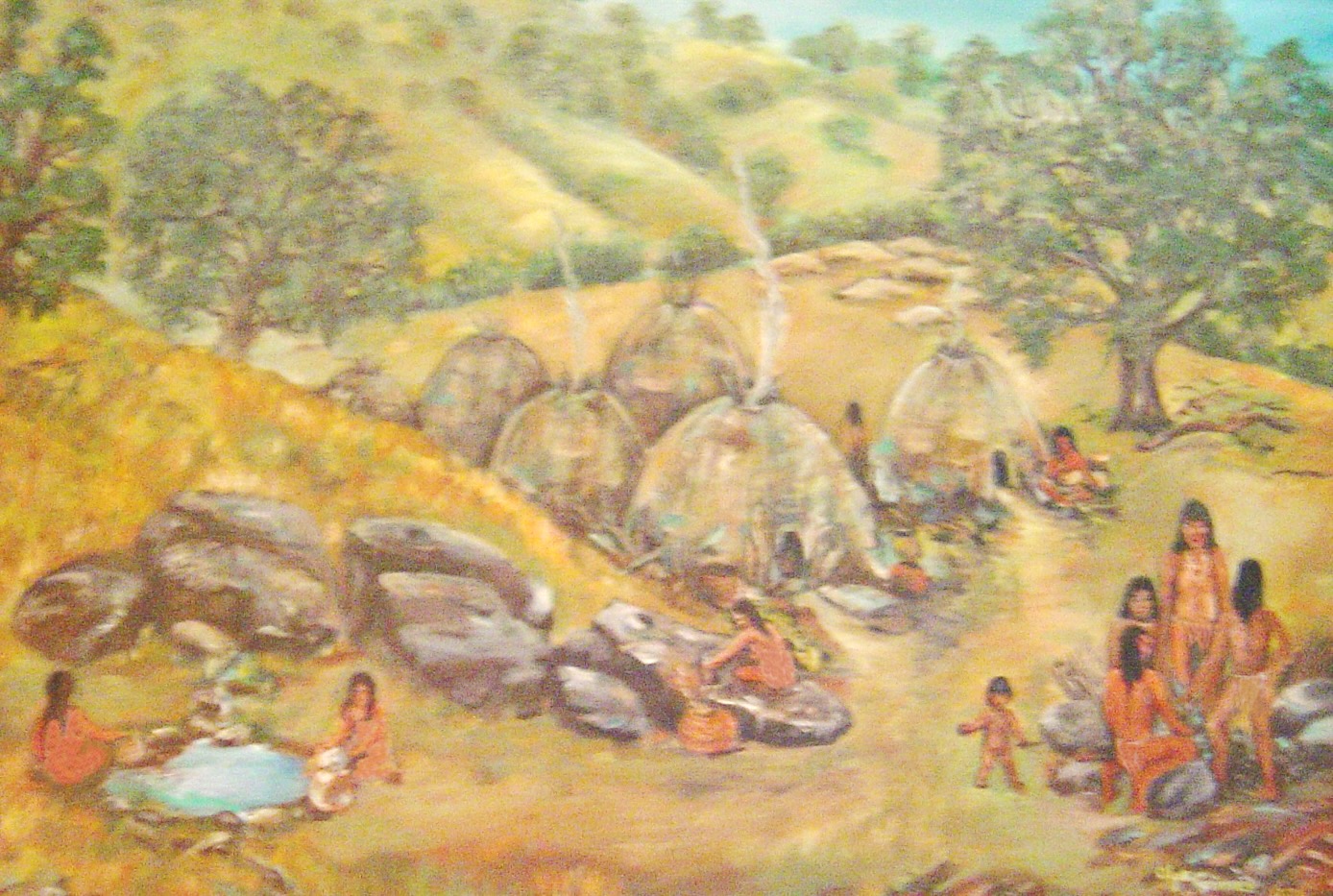

Traditional Bay Miwok homes were tule grass huts constructed using willow branches and tule grass which grew in the creeks. Willow branches are very pliable and can bend without breaking. The willow branches were pushed into the ground and then attached using willow bark to form a frame. Tule grasses from the creeks were layered over the frame to finish the home. Larger huts often could hold one or two families. Blankets of deer skin, bear skin, and woven rabbit skin lay around a central fire pit.

Groups of huts were often built near large pieces of bedrock where acorns were crushed with pestles in the making of acorn meal. Local villages in our area were all situated near creeks so water was readily available. In village settlements of 50-100 persons, each family took care of its own needs, making its own bows and arrows, baskets and nets, and hunting animals for meat and fishing for salmon and other fish. In the Bay Area, triblets usually had about 10 square miles of territory and sometimes spoke a different language or dialect so many individuals were multi-lingual and also used nonverbal communication.

Creeks were an important part of native life as they provided water for drinking, cooking and bathing. Fish such as salmon and steelhead, which were part of the native diet, were abundant in the creeks. Other animals came to the creeks for water so the Saklan were often able to capture them near the creeks.

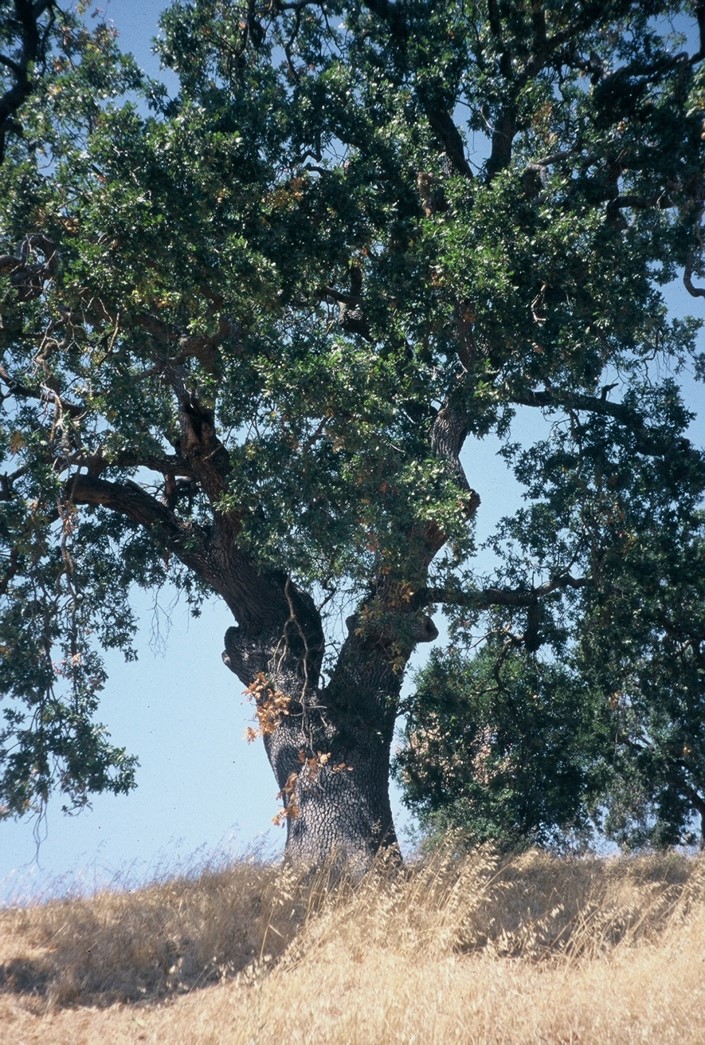

Indigenous trees and plants to this area include oak trees, soaproot, buckeye, willow, and bay laurel, and flowers such as poppies and lupine. Indigenous animals are foxes, raccoons, deer, bobcats, grizzly bears, and coyotes. Many of these plants and animals still exist here today.

The most important indigenous plants to the Saklan and neighboring tribes were the oak trees that grew in abundance in this area because they produced acorns, a staple food of the native people. There are two main types of oaks native to our area: the Coast Live Oak and the Valley Oak. The Coast Live Oak grows throughout the Bay Area. It has prickly leaves and produces smallish acorns. Although this tree loses many of its leaves in the fall and winter, it never loses all of its leaves. Live oaks can produce as many as 200 pounds of acorns each year. The Valley Oak occupies the inland valleys of our region. It has larger, flat leaves and produces bigger acorns. In Winter, all of its leaves have fallen off, leaving its branches bare. Valley oaks can produce around 350-500 pounds of acorns each year. A family could collect thousands of pounds of acorns during the harvest season.

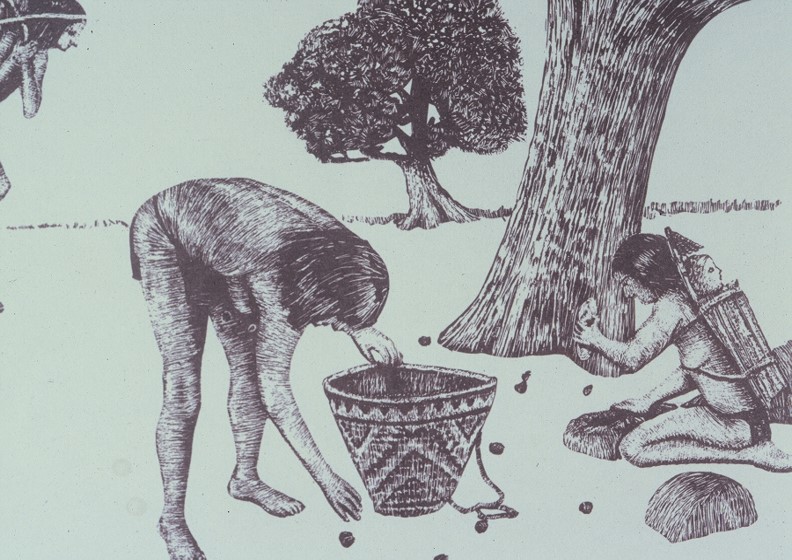

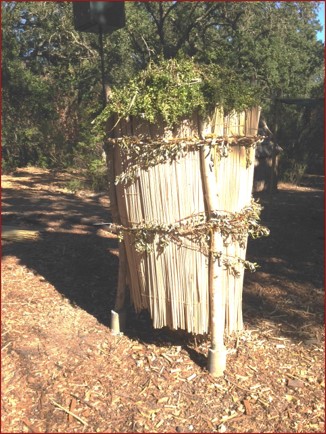

Each fall, the members of the tribe would all work together to collect as many acorns as possible. First, they would collect acorns from near the village, then go farther out to find more oak trees and more acorns. It was important to collect as many acorns as possible since they would have to last through the Winter, Spring and Summer until more acorns would be ripe again in the Fall. Other native animals depended on acorns for food as well. After the acorns were collected, they had to be saved for many months. Large storage baskets, called granaries, were constructed to hold the acorns. They were built to hold acorns away from the ground so that acorns wouldn’t get wet and moldy. The granaries were lined with bay laurel leaves to keep insects out. A top made of leaves or grass kept out other animals. Other Miwok tribes built different types of granaries but all were used to store the collected acorns. The type of granary that was constructed depended on the materials available to use.

Soaproot was another plant used by the Saklan. The root of the plant, resembling an onion, grows beneath the ground. When the leaves turn brown, the root can be pulled up and used as a food (if boiled) or as a soap to wash with. The tufts from the plant were used to make brushes.

Buckeyes are another indigenous plant that grows in the area. These plants produce a nut covered with a thick skin. When the skin was removed and the nut dried out, it could be used to help with fishing. When fish were found in creeks, parts of the creek were blocked off so the fish could not escape. Then pieces of chopped soaproot bulbs or mashed buckeyes would be thrown into the pool. A substance in the plants stunned the fish, which floated to the surface, unconscious but still completely edible. Other animals that were hunted as food were birds, deer, gophers, insects, lizards, snakes, moles, mice, ground squirrels, rabbits, raccoons, and foxes. The Saklan knew a great deal about how animals thought and acted and were expert animal trackers and hunters.

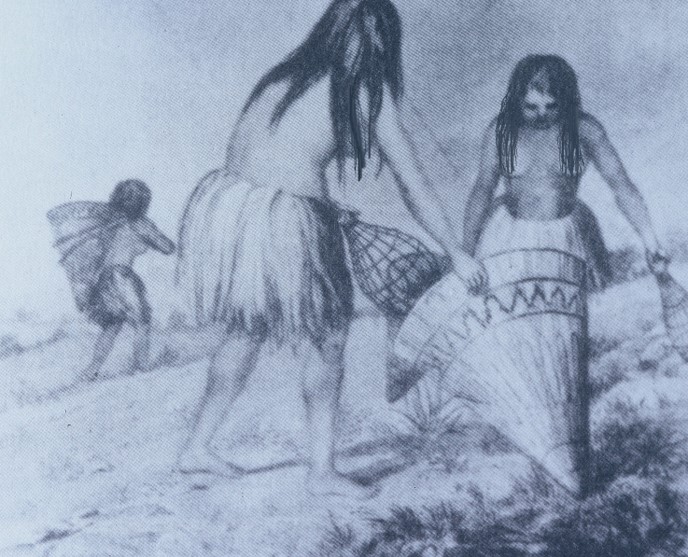

The Bay Miwok also collected seeds that grew in the area. In the fall when the seeds were ripe, they would use woven paddles to knock the seeds into their baskets and then would roast the seeds in the fire before eating them.

Flower stalks from deer grass or bunch grass were used to make baskets. Manzanita berries were used to make a cider that tasted like sour apples. The cider was used as a wash for poison oak and the leaves were chewed to reduce stomach aches. Elderberry leaves were used to make a poultice to reduce swelling from bee stings and the berries could be eaten raw. Wild ginger was used to fight infection.

The Arroyo willow was another important plant used by Bay Miwok people in several ways beyond its use in constructing homes. Tea made from willow leaves was used to alleviate pain and bark from the willow branches was used to tie things together. Willow bark was also used to make skirts which women tied around their waists. Bay Miwok women and men also wore deer skin skirts or breechcloths, and the pelts from grey fox, black-tailed jackrabbit, bobcat, raccoon and opossum could also be used for clothing or blankets. Necklaces made of shells and feathers were often worn by women. In the winter, mud might be smeared on men’s and women’s bodies to keep them warm.

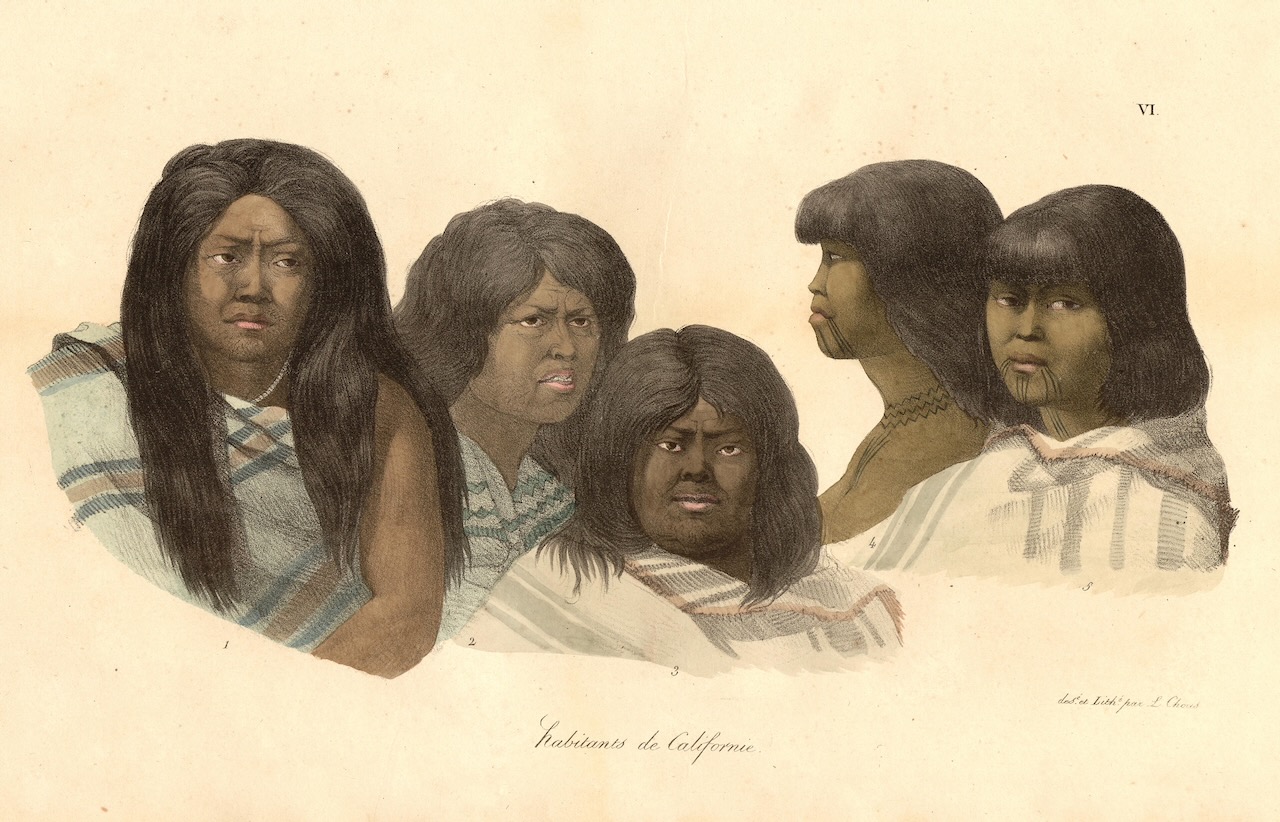

Bay Miwok men and women often wore tattoos on their bodies that told of their families or lineage. Some tattoos were decorative, some were the symbol of the image of the spirit meaning of an animal, bird or human being. Women and men wore their hair long, letting it grow throughout their life, although when someone in their tribe died, they would cut their hair as a sign of respect and mourning.

Throughout the year the people held various feasts, gatherings, and religious dances, many of them tied to the biological rhythms of the oak trees. The acorn harvest in the fall marked the beginning of the new year. Winter was spoken of as so many moons after the acorn harvest, summer as so many moons before the next acorn harvest.

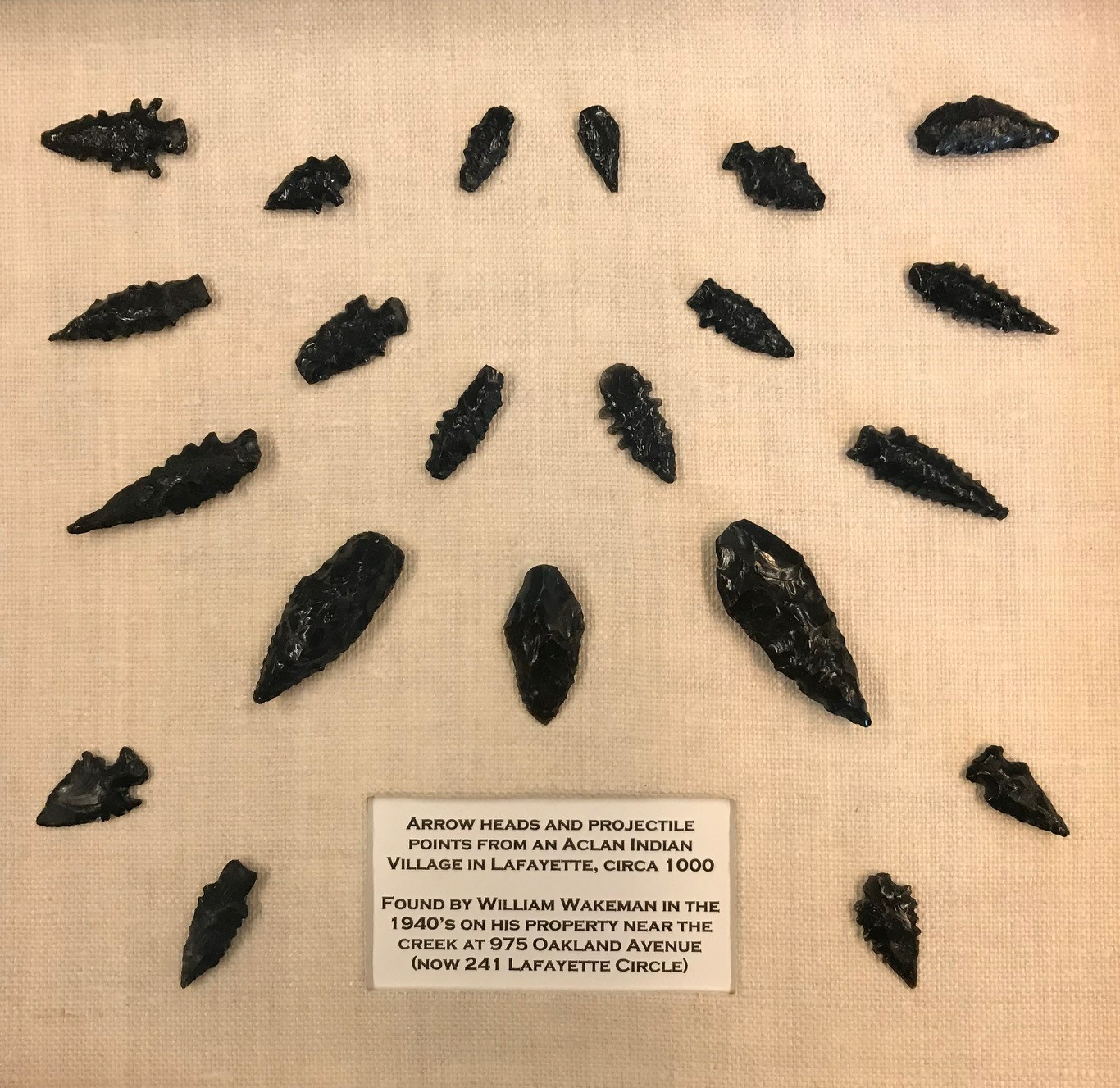

The Bay Miwok tribelets traded with other tribes for things they needed: soaproot could be traded for obsidian to make arrowheads; acorns could be traded with Coast Miwok tribes for shells to make necklaces. Obsidian trade among native tribes went on for over 4,000 years and was one of the earliest items of trade in California. Obsidian was used for arrows, spear points, knives and scrapers.

With the coming of European explorers who colonized the indigenous lands of North and South America, the Bay Miwok were displaced from their lands, enslaved by those who came, and often died from cruel treatment and disease in the Spanish Missions. Later when the Spanish settlers left California after being defeated by Mexican armies in the first half of the 19th Century, the Bay Miwok and other Bay Area tribes were further impeded from regaining autonomy over their lands by the large cattle ranches and rancheros that were created during the Rancho period and the subsequent Gold Rush that resulted in state-sanctioned slavery and murder of indigenous Californians.

Descendants of the Bay Miwok people continue to live in the Bay Area and beyond. It is important to learn about and appreciate indigenous people and their ways of life because they have stewarded the lands of this area for thousands of years, since the human world began according to their accounts of creation. By learning about the Bay Miwok cultures of the past, and about the Bay Miwok peoples today, it is hoped we might learn how to live in a closer way with other peoples and nature.

LAFAYETTE’S LAND ACKNOWLEDGMENT STATEMENT:

“We acknowledge that Lafayette is part of the unceded, ancestral homeland of the Bay Miwok people. The Bay Miwok and neighboring Ohlone people have lived in and moved through this place for thousands of years. They stewarded and shaped this land for hundreds of generations. We express our appreciation and gratitude for this profound legacy, which enhances and contributes to our lives to this day. We will strive to honor this land and strengthen our ties with the Indigenous communities that continue to live and work in our East Bay region as our neighbors and community members. We acknowledge and honor them and their ancestors, elders, and next seven generations.”